From an “epic” coming-of-age story to “delicious” dark academia – this is the very best fiction of the year.

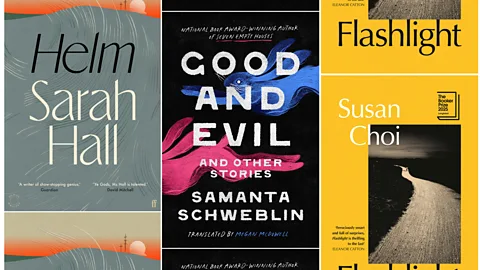

Helm by Sarah Hall

Hall is the author of novels including the Booker-nominated The Electric Michelangelo (2004) and 2021’s Burntcoat, and creator of several short-story collections. Weather and landscape have often been her concerns, as they are here, in a deeply researched historical “cli-fi” that took Hall the best part of 20 years to finish. The central character (and title) of Helm is Britain’s only named wind, which occurs in a particular part of Cumbria, where Hall grew up. She brings together strands that chart humankind’s attempts to master the wind, from prehistoric times to the present day, where her protagonist is Dr Selima Satur, a climatologist whose research suddenly makes headlines. “Helm is as vital, fierce and free as the phenomenon it describes,” writes the FT. The Guardian praises Hall’s “virtuosic” writing, “a tough and supple poetry anchored in decades of attention to Cumbrian land and plants and skies.” (RL)

Good and Evil and Other Stories by Samanta Schweblin

Each of the six stories in this collection by Argentinian author Samanta Schweblin features characters at pivotal moments that quickly shift to something deeply unsettling. A mother surfaces from a lake, having witnessed something awful; a young father is haunted by a moment of distraction that has had profound consequences; a lonely woman’s compassionate act is met with a frightening home invasion. From the opening “bravura” story onwards, says The Guardian, Schweblin “looks at the world directly, piercing its deceptive surface, allowing the reader to do the same”. The author’s “directness and clarity of language opens a unique emotional terrain where fear and compassion conjoin”. Good and Evil and Other Stories is, says Service95, a “a strange and unnerving collection of short stories”, and “the ‘horror’ here is subtle, psychological and deeply personal”. The stories “linger like a strange aftertaste, forcing anyone who reads to confront ambiguity, dread and the raw complexity of being human”. (LB)

Flashlight by Susan Choi

Ten-year-old Louisa is found on a beach in Japan, her father missing and presumed drowned, and from there the story unfolds across generations and continents, exploring Louisa’s family background that spans North Korea and the US. Shortlisted for the Booker Prize, Susan Choi’s sixth novel shifts genres from satire to drama, and from coming-of-age novel to international thriller. “Intricate, surprising and profound” is how it is described by the Booker judges. “It is a riveting exploration of identity, hidden truths, race, and national belonging” that “deftly cross-crosses continents and decades”. The author, they conclude, “balances historical tensions and intimate dramas with remarkable elegance”. Choi’s characterisation is “patient and sure-handed”, says the Times Literary Supplement. Flashlight is “epic” and “elegiac”. (LB)

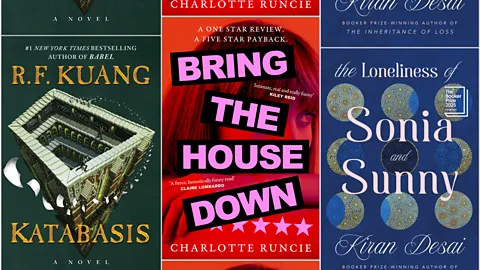

Katabasis by RF Kuang

Aged 29 and the author of six novels, including 2022 bestseller Babel and the viral 2023 hit, Yellowface, the prodigious and prolific Rebecca Kuang’s latest begins with a joke premise that “university is hell”. A dark academia/ fantasy likened to a cross between Dante’s Inferno and Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi, Katabasis (meaning descent into the underworld) begins in the leafy confines of Cambridge University. Having potentially killed her “magick” supervisor Professor Jacob Grimes in a lab experiment, post-grad Alice Law – followed by her student rival Peter Murdoch – travels to resurrect him, where she discovers that hell is a campus, and uncovers the full extent of the professor’s wrongdoings. “The heretical glee of this novel is irrepressible” writes The Guardian. Praising Kuang’s “delicious” sentences, The New York Times writes: “Katabasis shines with devastatingly real characters and absorbing world building”. (RL)

Bring the House Down by Charlotte Runcie

A debut novel by arts journalist Charlotte Runcie, Bring the House Down explores the relationship between artist and critic, and the themes of female rage and cancel culture. Taking place over four weeks at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival, the story centres around theatre critic Alex, his colleague – and our narrator – Sophie, and the creator of a one-woman show, Hayley. Events unfurl when Alex writes a damning review of Hayley’s show, but then proceeds to sleep with her before the review is published. The Los Angeles Times describes it as “deeply entertaining” and “delightfully snackable”, while the Chicago Review of Books says it is “a turbulent and harrowing ride on what it really means to criticise a culture”. It adds: “the difficult genius of Bring the House Down is how hard it hammers the idea of there really being two sides to every story”. It is a “formidable debut novel”. (LB)

The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny by Kiran Desai

After a gap of nearly 20 years, Desai, the author of Hullabaloo in the Guava Orchard (1998) and the Booker and National Book Award-winning The Inheritance of Loss (2006), has returned with a sprawling but acclaimed novel – also shortlisted for this year’s Booker. Ambitious New York-based journalist Sunny and fiction-writer Sonia, a lonely student at a Vermont university, meet on board a train. Their families have already made a botched attempt at matchmaking – which drives a wedge between them. Many other obstacles get in the way of their relationship in a novel that concerns love and family, identity and postcolonial history, wealth gaps and creativity, in a huge, 700-page work that is genre-bending and intensely detailed. “Capacious and shapeshifting” and “immensely entertaining” writes The Guardian of the novel. “Crowded but never claustrophobic”, writes The New York Times, “The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny is among those most rarefied books: better company than real-life people.” (RL)

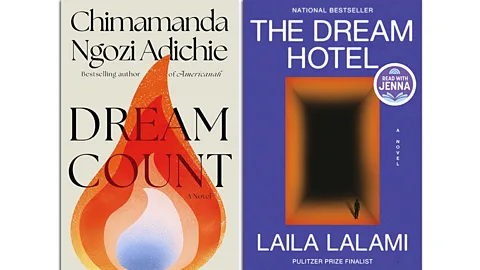

Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

More than 10 years have passed since Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s acclaimed Americanah, so the arrival of her new novel is a big literary moment. Dream Count is built around interconnecting storylines and the friendship of three Nigerian women whose lives have not worked out as they had envisioned. Recounting the characters’ hopes and struggles, the novel interweaves childhood and early-adult memories with the women’s current lives. It is “worth the wait,” says The Observer, and is like “four novels for the price of one, each of them powered by the simple but evergreen thrill of time spent in the company of flesh and blood characters lavishly imagined in the round.” The book explores “big themes” according to the New Statesman – masculinity, race, colonialism, power. “A complex, multi-layered beauty of a book. Extraordinary. ” (LB)

We Do Not Part by Han Kang

We Do Not Part was released in English translation in February, although it was originally published in Han Kang’s native South Korea in 2021, and therefore helped contribute to the body of work that won her the 2024 Nobel Prize for Literature. Drawing comparisons with her Booker Prize-winning bestseller, The Vegetarian, and similarly blurring the lines between dreams and reality, We Do Not Part explores the relationship between two women, Kyungha and Inseon, while uncovering a violent and forgotten chapter in Korean history. The LA Times calls We Do Not Part: “exquisite and profoundly disquieting”. It writes of Han Kang: “her singular ability to find connections between body and soul and to experiment with form and style, are what makes her one of the world’s most important writers.” (RL)

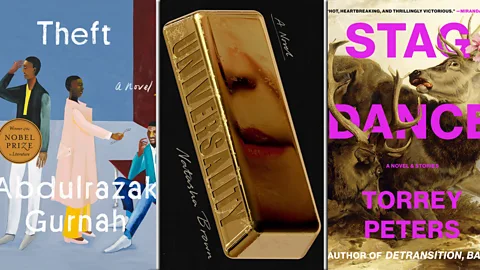

Stag Dance by Torrey Peters

The follow-up to Torrey Peters’ critically acclaimed debut Detransition, Baby is a collection of tales, each with an intriguing premise, ranging in genre from romantic to dystopian to historical. In The Masker, a young party-goer on a hedonistic Las Vegas weekend must choose between two guides, a mystery man or a veteran trans woman; in The Chaser an illicit boarding-school romance surfaces; in the titular Stag Dance a group of lumberjacks in the 19th Century, working deep in the forest, plan a winter dance – with some of the men volunteering to attend as women. The Chicago Review of Books compares the collection favourably to Peters’ debut, describing the stories as “seductive, dazzling, and history-making once again”. The Guardian is similarly effusive: “The pieces are meticulously crafted; especially Stag Dance, with its deft pacing and almost operatic denouement.” The writing is “mischievous rather than sanctimonious”, it adds, and “it is clear she is having a great deal of fun”. (LB)

Theft by Abdulrazak Gurnah

“A quietly powerful demonstration of storytelling mastery” writes The Observer of Theft, the 11th novel from the 2021 winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature. Set against the backdrop of postcolonial East Africa, situated between Zanzibar and Dar-Es Salaam, Tanzania, Theft is a coming-of-age tale exploring the inner lives of three teenagers – Karim, Badar and Fauzia – who bond despite growing up in very different circumstances. “A tightly focussed, beautifully controlled examination of friendship and betrayal,” writes The Economist, while The Wall Street Journal praises Gurnah’s “restraint”, adding: “he builds his fictional worlds cumulatively, giving equal regard to the ‘many things’ that make up experience. There are no single truths in this steady, mature novel, which may be why it feels so true as a whole.” (RL)

Universality by Natasha Brown

Natasha Brown’s celebrated 2021 debut, Assembly, was a short, precise novel and a dissection of class and race that was shortlisted for several awards. In her follow-up she examines how identity politics is cynically deployed, satirising on the way cancel culture and the worlds of publishing and journalism. The story begins with a dubious article attempting to unravel a mystery involving an illegal rave, a missing gold bar and a banker. Soon the novel moves on to the fallout from the exposé, and the knock-on effect of the people affected by the crime. “It’s all enormous, nasty fun,” says the Literary Review. “Infidelity, exploitation and hatred abound… Brown’s main purpose is to satirise and skewer the socio-economic forces that have shaped life in the UK since the late 2010s.” Universality is “very funny”, says the New Statesman. “Brown is an astute political observer, easily dismembering cancel culture and our media circus.” (LB)

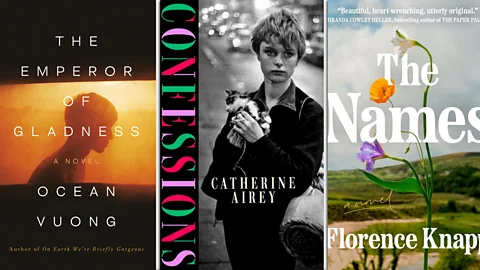

The Names by Florence Knapp

Knapp’s debut novel begins in 1987, as Cora Atkin is pondering three different names for her newborn baby boy: Gordon, after her abusive doctor husband; Bear, the choice of her older daughter, Maia; or her preference, Julian. With the premise that each potential name offers a unique destiny, the narrative splits therein, revisiting its characters at seven-year intervals in a manner that recalls Sliding Doors. And despite its dark subject matter, critics have praised The Names for its upbeat, uplifting effect. The Standard writes: “Knapp’s deftly woven story is at once a big, bold experiment, a playful exercise in nominative determinism, a meditation on fate and a coming-of-age story”, while The Washington Post calls the novel: “a profound, deeply compassionate examination of domestic abuse,” which is “startlingly joyful and paced like a thriller”. (RL)

The Emperor of Gladness by Ocean Vuong

Ocean Vuong’s second novel The Emperor of Gladness: “may well be the first millennial Great American Novel”, according to Art Review. It is: “perfectly tuned”, and “as wide in scope as it is quiet and tender”. It tells the story of Hai, a young gay man who has run away from home, and his coming of age in the rural northeast in Obama-era US. It also explores his friendship with Grazina, an elderly Lithuanian widow with dementia. Hai finds work in a fast-dining chain, and bonds with his mixed bag of new colleagues, who discover connection in their past hardships. The Emperor of Gladness is: “a fine-grained social panorama driven by the developing camaraderie of an ensemble cast bonded in precariousness and pain,” says The Observer. (LB)

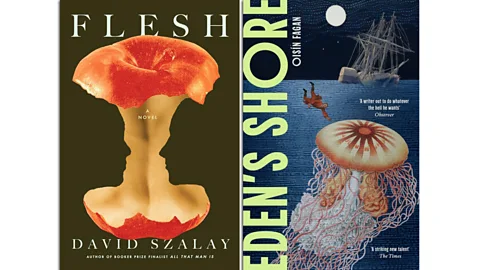

Eden’s Shore by Oisín Fagan

“A tremendous romp of a tale“, this brutal seafaring epic’s protagonist is Angel Kelly, a late-18th-Century slaver headed to Brazil with the goal to found a utopian community; chaos ensues and he washes up on the shores of an unnamed Spanish colony. With grisly attention to detail, Fagan spares little in describing the violence of the slave trade with the blackest of humour and an experimental approach to form. “Eden’s Shore is a rich and beautifully told tale of toxic adventurism” writes the TLS, while the Financial Times writes: “Alexander’s capacious performance is made to encompass the visceral, physical experiences of the journey – disease, sex, seasickness, violence – and its more cerebral aspects, in which the politics, philosophy and idealistic utopianism of the day find expression.” (RL)

Dream State by Eric Puchner

A multi-generational family saga, Dream State explores themes of love, betrayal, and the effects across generations of the choices we make. Beginning in 2004, the story is set in a rapidly warming, fictionalised version of Montana’s Flathead Valley, with the lake at the valley’s centre the nucleus of the story. Dream State traverses five decades, and: “gradually coalesces into a family history that feels monumental”, says Lit Hub. The effect is: “hypnotically telescopic, a vision of people we come to know across decades. Puchner’s manipulation of time is among his novel’s most magical elements.” His narration: “can slip from funny to harrowing as fast as young man can ski to his death”. Oprah Winfrey selected Dream State as a book club pick, describing Puchner as a “master storyteller” and the book as: “an exquisite examination of the most important relationships we have in our lives”. (LB)

The Dream Hotel by Laila Lalami

Longlisted for the 2025 Women’s Prize for Fiction, Lalami’s fifth novel is a nightmarish speculative tale about the terrifying reaches of technology and surveillance. As Sara returns to LAX airport from a conference, she is stopped by the Risk Assessment Administration, who determine – using data from her dreams – that she is about to harm her husband. She’s transferred to a retention centre to be monitored for 21 days, where she finds – along with other dreamers – that her journey back to her family becomes more and more out of reach. “A scarily credible vision,” The Spectator writes of The Dream Hotel, continuing that it: “taps deftly into the terrors of our times”, while The Economist calls it: “a riveting tale of the risks of surrendering privacy for convenience”. (RL)

Confessions by Catherine Airey

The debut from new voice Catherine Airey has been widely praised. Confessions traces the trajectories of three generations of women as they experience the weight of the past in all its complexity. In 2001, newly orphaned by 9/11, New Yorker Cora Brady, on the cusp of adulthood, is offered a new life in Ireland – where her parents grew up – by an estranged aunt. “The narrative zips along with the crackling intelligence of Donna Tartt, full of twists and zips, and genuine surprises,” says the Irish Independent. “Confessions is an astonishing and remarkable novel and truly deserving of all the accolades coming its way.” The Guardian says: “The book is a saga: its serious pleasures are its expansiveness and range, and Airey’s rare, particular instinct for scenes or worlds that are interesting to be with, from 1970s New York art kids to early female gamers.” Confessions, it concludes, is “a cool, bold image of female pain and liberation”. (LB)

Flesh by David Szalay

Szalay’s most celebrated work, All That Man Is, which was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 2016, explored 21st-Century manhood through the lives of nine different men. One man’s journey from teen to adulthood is the subject of Flesh. We first meet 15-year-old István in Hungary where he lives with his mother, then as he begins a relationship with a much older woman that has tragic consequences, joins the army and then rises to the top of London society. With Flesh, Szalay employs an even more pared-down version of his spare, minimalist prose to explore the meaning of a life. “Flesh is about more than just the things that go unsaid…” writes the Guardian, “it is also about what is fundamentally unsayable, the ineffable things that sit at the centre of every life, hovering beyond the reach of language.” The Observer praises Flesh’s: “searing insight into the way we live now” calling it: “a masterpiece”. (RL)

Credit: BBC